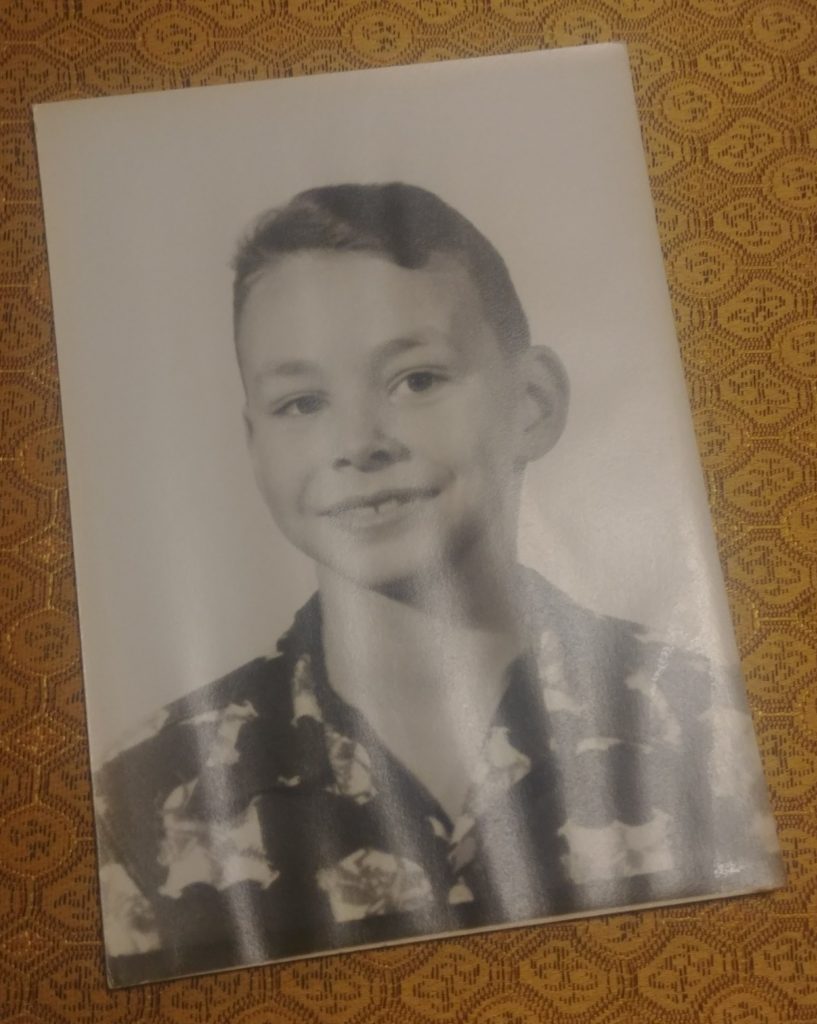

When I was eight years old, my father sat me down and said, “We should talk about what you want to be when you grow up.”

It turned out there were only three things a man wants from a career. He wants to make a decent living, a reasonable amount of money, so that he can support a family and live well. He wants respect of his peers and the community. And he wants to feel that what he is doing is of value, that it’s worthwhile.

So Dad started with the manual laborer, the guy digging ditches or shoveling coal. He doesn’t make much money, barely enough to live on. And sure, he deserves respect for working hard and being a good person, but really, how much respect is he going to get? Not much. And finally, is he doing something worthwhile? We need ditches dug and we need coal shoveled. But anybody could be doing that. It’s not like it’s special work.

So next we considered, or Dad considered, the trades. You could be a carpenter, or a plumber, or an electrician. Men working in the trades make a bit more money, but not all that much more, not enough to live in a big house and drive a new car every year. It’s still generally hard, dirty work. As for respect, a good tradesman is valued. People appreciate his work, and he gets a little more respect. But still, he’s “just” a plumber or an electrician. Nobody special.

That brought Dad to talk about the professions. In 1958 when this conversation was happening, there were only three professions. Can you name them? Nobody can name all three.

Everybody gets that one of the professions was law, and one was medicine. Nobody can name the third. And no, it wasn’t teacher or chiropractor or salesman or writer or artist…. it was….the clergy.

Those were the big three: doctor, lawyer, and priest. And being in one of the professions made you a somebody.

My father hated lawyers. They were just scum of the earth, dishonest, no integrity, and it didn’t matter how much money they made he wasn’t going to give them any respect. So forget being a lawyer.

Being a priest was a good thing, an honourable thing, but it’s not much of a life. Too much time attending tea parties and officiating at marriages. A secure living, but not a lot of money. No, you wouldn’t want to be a priest.

But a doctor? Now there was something to aspire to. Talk about the respect of your peers! A doctor is treated almost like a god. (Yeah, I know, but this was in 1958). You check into a hotel and it’s, “Will you be getting any calls, Doctor.” Make a reservation at a restaurant and it’s, “Oh doctor Scott, so good to see you here. We’ve got a good table for you.” And money. My god, a doctor can earn as much as fifty thousand dollars a week. (Again, this was 1958 when a new car cost three thousand dollars; when my father might have been making eleven thousand a year as middle management of an insurance company.)

As for doing something of value, what could be more valuable than saving lives, life and death.

So it was decided. From that day on, I was going to be a doctor. My father warned me that I had to start getting ready for this career now, because if I didn’t I’d never make it. There was too much competition. My future, my destiny, was set.

For my twelfth birthday I asked for, and was duly given, a copy of “Blacks Medical Dictionary”. I cultivated an attitude and solemn authority that I assumed a doctor should have. By fourteen, I had a good bedside manner.

And then I hit the teenage identity crisis. I found myself at university in pre-med, arguing with people who were far smarter than me, with far more life experience, and I found my fathers words and attitudes coming out of my mouth. Suddenly, everything I thought about myself and the world was open to question. I had no ideas of my own, no viewpoint of my own. I didn’t know what I was talking about.

In my father’s eyes, I was right off the rails. What do you do with a kid like that? You send him to Europe to let him sort himself out and get his head on straight. To be clear here, this was incredibly generous of my father. He was not a wealthy man. He worked hard, and paid for what needed paying for, but he was always under serious financial pressure. I will always be forever grateful for that trip to England to meet my Aunt Mary and Uncle David, my mother’s brother and his wife, and then on to France, Holland, and Germany. I spent endless hours in the Louvre, and in the Rembrandt Museum in Amsterdam, and someplace else where I could admire the Rodin sculptures in the flesh. I will never forget the unrestored Opern Platz in Frankfurt, bombed to a shell by the Brits during the war because the Nazis had holed up in the basement, or the castle at Konigstein, with granite steps worn to a slippery ramp by centuries of leather shoe soles. It was a great trip, complete with shipboard romances and my first experience of having sex in an actual bed. With an actual woman.

After a couple of months of desperate loneliness and soul searching, my head was a straight as it was ever going to get. And the conclusion I reached was that I didn’t want to be a doctor. That was my father’s ambition, not mine. So, what did I want to be?

I have always loved literature and admired writing. Ah hah! That’s it. I’ll be a writer.

I told my father that I didn’t want to be a doctor. I wanted to be a writer. He said,”Well, congratulations. You have chosen the only career I can think of that’s harder than selling life insurance.” And I knew he was right.

From where I sit today, an old man, I can’t think of anything dumber for me to want to be. The thing is, I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t necessarily want to write. Writing is hard work. I didn’t even like writing. Still don’t. I didn’t want to be a journalist, or the writer of advertising copy or equipment manuals. I wanted to be a novelist. But… let’s get real. Nobody was buying short stories. Writing a novel took years of lonely, dedicated effort with a tiny possibility of success after all that work. Besides, I had no idea what to write about. I recognized that I got a good idea once in a while, maybe every five years, but I didn’t have what it takes to be a novelist. I might be able to bullshit the world that I was a writer, but I knew the truth.

Looking at the world in a slightly more realistic frame of mind I decided that the big market for non-fiction writing was not short stories or novels. The market now was film and television. So I joined the Simon Fraser University Film Workshop to learn more about film and television and my fate was sealed.

I still wanted to be a writer, to tell powerful, inspiring stories. But I could make a living doing technical work like sound recording and editing while I wrote scripts and worked toward becoming a director, the author of the movie.

For years, as I struggled with financial insecurity and self doubt while trying to write, produce, or direct something meaningful, I would lie awake at night in horror at having wasted my life. I was supposed to be a doctor. Too late now to chose a different path. A profound despair would close in on me, a feeling of loss, regret, unleavened by any redeeming consideration. Fool. Loser.